FULL CONCEPT

A Normal Family.

From Charles Addams first cartoons of them in the New Yorker, the then unnamed eponymic family and characters not only played with the macabre but highlighted the oddities of life. His creations were ghoulish. Their perspective and approaches were strange. Yet still, they were a happy family in a loving household. Husband and wife were utterly devoted to one another. The children played together and were tucked into bed. Grandmothers and uncles had an active role in the life of the family. They cooked together, shared hobbies, celebrated their ancestry, the kids went to camp, the pets cared for, chores managed. In general, a home was observed—albeit a wealthy one with a butler. Of course, how these observations were handled was anything but the typical depiction, they are the Addams, after all. They made a family with morbid acts, grotesque interests, under the perspective of a memento mori. The mother asks a neighbor for a cup of poison. The daughter beheads her own dolls. The son collects warning signs in his room. The father is supposed to be kicked, not kissed, before bedtime.

From their inception, comparison to ‘normality’ sits at the heart of every Addams’ story. It’s a clever juxtaposition and consistent formula. Bring in the status quo for conflict and take us on a journey that demonstrates how they cope; how different they are. How do they respond to carolers? To door-to-door salesmen? To horror films? Then reveal to us that the so-called normal people on the outside, are indeed the creepy ones within. And truth be told, no one comes from a ‘normal’ home. Every family has its quirks, perhaps most not a severe as the titular family, but that’s what makes a home unique. Beyond Stepford and sitcoms, that standard nuclear family, is more fictitious than the Addams. Who doesn’t have a black sheep uncle? Whose house doesn’t have strange traditions that unite them? Whose clan isn’t peculiar, that we, as a part of them, see as dear.

Thus, we end up rooting for the odd-ball Addams and not the other characters, stand ins for orthodoxy. When those regular people march to the Addams residence, they represent conformity and control, societal pressures, and impossible standards. These are the antagonists of the Addams, demanding that they change and fit their lives into pre-approved Tupperware. They are the hypocritical forces, the shallow forces, the ‘right’ forces, which on the surface display the ideals, give the appearance of normalcy, the so-called Joneses of whom with all must keep up; yet are hollow for it. They made a trade the Addams time and time again refuse. Giving up a part of their soul to conform. And despite how twisted the Addams’s are, it is the visitors who are more mangled and distorted. Look no further than the Beineke’s, the control freak husband and a deeply repressed wife of Mal and Alice, who together create Malice. Characters who, given the Addams’s dramatic track record, will either enter the fold, run scared, or be buried by it. There is a great deal of pleasure and plot to be gleaned from the Addams’s living their lives in opposition to what we are told to be. Much of the Addams’s humor derives from their disregard for normalcy or immunity to it. It also makes us like them more: their unspoken representation of the marginalized, their weird-shielded utopic family life, their contrast that reveals the cynicism and sinisterness in Normal Rockwell.

But The Addams Family Musical takes one important step forward which elevates it beyond the rest, one that no other Addams’s stories succeed in: It challenges the Addams with their own status quo as well. Like the Simpsons, they are an immortal cartoon family. Nothing, it seems, will ever change those dynamics. However, the musical, intentionally shakes up their dynamic. Morticia, the head of the family, is made to feel powerless. Gomez her devoted husband, is forced to betray her trust. Wednesday, the lost soul, must reconcile with love. And even Pugsley, is pushed to consider a world without his eternal playmate and tormentor. All inversions, challenges for them individually and for the family together, seen most prominently in the battle between their core: Morticia and Gomez. This is catalyzed by Wednesday and Lucas’s engagement, an event that, although positive for most, always marks change. In fact, beyond marriage (and perhaps a new child) only death changes a family more. Considering the Addams’s unique perspective on the grave, however, that death does not prevent participation in family life, a martial union stands as the singular event which could cause change in the home.

And so, despite all gloomy and creepy shenanigans, The Addams Family musical is about a normal family at an infection point. It is about those things which make a family: love, trust, tradition, and togetherness. Will they change and meet the moment? Or will the paragons of unorthodoxy fail to shift themselves both for good and bad, for happy and for sad? And how, will the strangest family in all fiction pull it off if they do?

A Love Story.

Nobody goes home, or back to the grave, until love triumphs. That’s the condition Fester outlines at the start of the conflict. It’s not a difficult proviso to understand. On the surface, before the complications naturally arise, the romantic hurdle is one for Wednesday and Lucas alone. Yet like a monkey’s paw, it is just vague enough to encompass more. In fact, the ancestors cannot rest until all love succeeds. This includes the obvious classic young lovers from differing households, whose struggles circle around that worrisome issue of compatibility. It also includes masters of passion, and representation of healthy commitments, Morticia and Gomez, who must reignite what they have always had, following an unexpected dampening. The dysfunctional Bieneke’s are also roped in as the third of the triad couples. Theirs is a story of stagnation and rediscovery.

Wonderfully, the couples’ journeys are not independent from another; they influence, contrast, and jar each into a better position. The budding love sparks disapproval and dissatisfaction in the other couples. The Beineke’s, stewards of standards, of course offer a counterpoint to Gomez and Morticia, but also act as the second of two options for the Addams patriarch and matriarch when paired with Wednesday and Lucas: stagnant or rekindle. While they and the engaged couple, for the Beineke’s, serve as healthy and inspiring models of relationship. The key relationship is not the new lovebirds, nor the couple in desperate need of therapy, but Morticia and Gomez. Where he guides the couple, at times haplessly, she stands in opposition. This is also seen in how they influence other characters. Morticia’s growing disappointment over Gomez has positive impact on Alice. Mal too, perhaps, subtely benefits from conversations with Gomez. But narratively, it is the Addams parents which start and end the play.

The conflict is best exemplified by Morticia and Gomez’s disagreement and opposition to one another, and it is their potential failure which serves as the climax of the play. Will Morticia leave? Can Gomez make amends and rebuild trust? How will their love triumph? Though, the love that must triumph is not exclusively romantic, not seen just in the couples. All love must succeed. This includes love which is non-traditional, (a la Fester’s affection for the moon), love between siblings and platonic love (Pugsley’s dilemma), and last, which serves as the true center piece of the show, familial love.

The love which binds a family through trying times and holds together despite external and internal conflicts. Only through this, the confession and subsequent celebration of Pugsley, the bravery of Wednesday’s apology and request for a blessing, the honesty and lengths of Gomez, and the acceptance and relinquishment of power of Morticia, are conflicts finally put to rest. And it is the love of family, a love that is truly unique for each family, non-more so uniquely expressed, but ultimately conventional, than the Addams, with equal parts truth, acceptance, care, and hope, which ultimately triumphs.

Meet the Addams.

They're creepy and they're kooky,

Mysterious and spooky,

They're all together ooky,

The Addams Family

Their house is a museum,

When people come to see 'em

They really are a screa-um

The Addams Family

So get a witch's shawl on,

A broomstick you can crawl on.

We're going to make a call on

The Addams Family

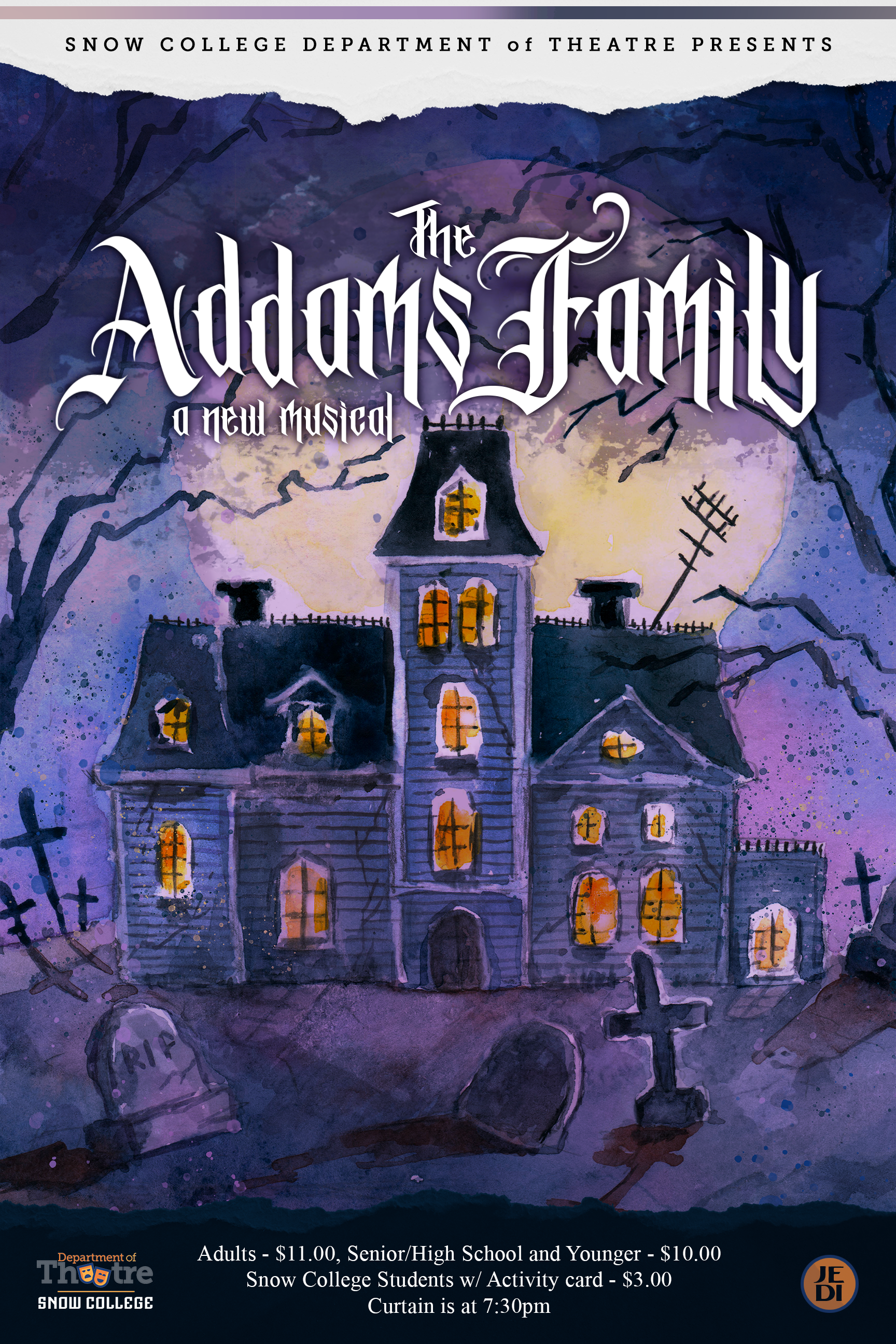

Charles Addams first introduced us to the family which later took his name, in single panel, page nine cartoons in the New Yorker. Over the years the collection of lunatics formed into a family. Along the way, we got to see a skewed perspective on everyday life and the delightful ink-washed world of his characters. They were not crystalized as we know them today, however, until a television executive saw a collection of Addams work and decided it would make for a great show and counter-programming to the upcoming CBS program, The Munsters.

Like the 1991 movie, Addams himself had creative input into that show’s depiction of his creation. Taking from his years of work, he created character descriptions which still serve as the story-bible for Addams Family narratives. While not everything he desired occurred (notably Gomez and Pugsley, were originally to be named, Repeli and Pubert), it’s rare to have character outlines that span an adaptation process. Included below are his notes, the who’s who of the Addams and how they function as a family.

Morticia: The real head of the family... low-voiced, incisive and subtle, smiles are rare... ruined beauty... contemptuous and original and with fierce family loyalty... even in disposition, muted, witty, sometimes deadly... given to low-keyed rhapsodies about her garden of deadly nightshade, henbane and dwarf's hair...

Gomez: Husband to Morticia, if indeed they are married at all... a crafty schemer, but also a jolly man in his own way... though sometimes misguided... sentimental and often puckish - optimistic, he is in full enthusiasm for his dreadful plots... is sometimes seen in a rather formal dressing gown... the only one who smokes.

Wednesday: Child of woe is wan and delicate...sensitive and on the quiet side, she loves the picnics and outings to the underground caverns...loves the color black...a solemn child, prim in dress and, on the whole, pretty lost...secretive and imaginative, poetic, seems underprivileged and given to occasional tantrums...has six toes on one foot..."

Pugsley: An energetic monster of a boy, about nine years old, blond red hair, popped blue eyes and a dedicated troublemaker, in other words the kid next door. A genius in his own way, he makes toy guillotines, full size racks, threatens to poison his sister, can turn himself into a Mr. Hyde with an ordinary chemical set.

Grandmama: This disrespectful old hag is the mother of Gomez... she willingly helps with the dishes, cheats at solitaire and is roughly dishonest... the complexion is dark, the hair is white and frizzy and uncombed... she has a light beard and a large mole... foolishly good-natured... fumbling, weak character... is easily fooled.

Uncle Fester: Uncle Fester is incorrigible and, except for the good nature of the family and the ignorance of the police, would ordinarily be under lock and key... the eyes are pig-like and deeply embedded... he likes to fish, but usually employs dynamite... he keeps falcons on the roof which he uses for hunting... his one costume, summer and winter, is a black great coat with an enormous collar... he is fat with pudgy little hands and feet.

Lurch: This towering mute has been shambling around the house forever... He is not a very good butler but a faithful one... One eye is opaque, the scanty hair is damply clinging to his narrow flat head... generally the family regards him as something of a joke.

While these characters originated in the New Yorker, the television series brought them to life. Thing, for example, a hand that changed records in a single cartoon, became further removed from its original depiction in the tv show. This move from cartoon to live-action, grounded the Addams and created a playful dissonance. Suddenly the strangest family were, in fact, real. Unlike the Flintstones, television’s cartoon first family, who dealt with modern life in a prehistoric setting, or the contemporary Munsters, which melded a family together from classical universal monster movies, by their very premise, The Addams Family resisted the nature of a sitcom premises, moreso than its high-concept kin such as Green Acres, Bewitched, and I Dream of Genie. The show followed the tropes and style of the time, but its satirical nature could not be diminished. If Pugsley were take in a stray as a pet, it would be an escaped gorilla from the zoo, and he’d teach it to serve tea. When the pipes in the house break, and their insurance is cancelled, Fester becomes an insurance salesman and gives out a policy his boss doesn’t approve of. As it turns out, it’s not an issue, as the boss finds out that Gomez owns the whole insurance company.

Unlike the other sitcoms, the relationships were more modern. Gomez and Morticia expressed love physically albeit flamboyantly (which was over the top enough it passed through censors). Their marriage was that of equals, who trusted and shared each other’s passions. Gender roles were never the standard. Gomez couldn’t drive. Morticia was hardly a homemaker. And best of all, they never felt they needed to hide or change themselves around outsiders.

While iterations of the Addams would continue past the 1960s series, their next cultural moment would occur in the 90s, when the family would burst onto the silver screen. Their first cinematic outing, The Addams Family, pays homage to the cartoons in its first teasing shot, as the Addams prepare a cauldron of presumably hot oil to rain down upon Christmas carolers, an image taken right from the New Yorker. From that point on every scene cements the dilapidated style, gothic influence, and gloomy atmosphere, with enormous attention to detail and cobwebs alike. It’s a look and feel the comics and series could only hint at, but now audiences expect.

Truly it is the sequel, Addams Family Values, which shares the best narrative structure of the musical. Change occurs in the unchanging family with the addition of a new Addams and the engagement of Uncle Fester. After decades, the Addams were being moved more out of their comfort zones and their preconceived notions of family. Yet, this story, like its predecessor, relies on an external force to motivate much of the plot. The internal family conflict of Wednesday’s engagement truly sets the musical a part.

In recent years, the animated movies have continued keep the Addams in the zeitgeist. Aimed at far younger audiences, these films are at best adequate for entertaining children with flashy, outrageous colors of ‘normal people’, some jokes from the original Addams cartoons, but are mostly a filled with pandering content, overly juvenile gags, and a design aesthetic which is supposed to evoke the original work. Instead, these movies are knock-offs, the same brand of work such as The Lorax or The Grinch, from creatively impaired individuals, and certainly not work we should follow, or to which aspire. One lesson might be learned from the follies: the character models of Charles Addams, clearly, are not the sole way forward either.

The Addams work best dramatically when they are people, not cartoons. When they interact with individuals who are equally not caricatures themselves. Outlandish? Yes. Eccentric? Yes. Unrealistic? Not so much, and for good reason. In the musical, The Addams are given genuinely relatable problems, and for an audience to buy in fully, those dilemmas must stir genuine and grounded emotions in the Addams. The outside might be absurd: a fat bald person with no discernable sexuality falling in the love with moon, a wife threatening separation over her husband’s reasonable omission, a test of love with a crossbow, blindfold, and apple; but the motivation and heart behind them should be as real as the everyday. A person falls in love. Discord strikes a marriage. We must be brave to find happiness with others.

Grounded truth is not the only reason to handle the Addams with care. They are coded as rich and liberal but also European and Jewish. Push too far and relatability is lost, stereotype may take over, and frankly, some might not get beyond just laughing at the Addams, deriding them as ‘other’. The Beineke’s are equally susceptible to this, their antithesis, conservative Christian Midwesterners, with all the trappings of middle class sneering over picket fences.

Striking the balance of exaggeration and reality will constantly be a touchstone in the process. Within their kooky world, we must find the Addams’s version of verisimilitude. Actors may gravitate to overplayed performances when subtlety and ease better contrast the heightened style. When a phone is used, it can’t look like it has come from Amazon, just the same, it must be believably a phone—one that fits the family. Their house must be in some way a museum which expresses all their wealth and quirk and heart, without blowing the budget on full-scale maximalism. And the costumes and makeup can be playful, but still remind us that the Addams are people—just like us—on the inside, beyond the viscera they so enjoy.

The Dead People.

Addams’s characters are not the only family members we see. Populating the world are the risen ancestors, forced to walk the living world until all again is made right. The script makes mention of who these people once were, a caveman, a flapper, a soldier, etc. (All no doubt dead thanks to a gloriously awful death, as one might imagine is Addams tradition). From a flight attendant to a conquistador, saloon girl to pilgrim, a theme emerges from these ghosts: they are the Addams with connection to America. (The West End production is fascinating as they made the ancestors reflective of other cultures too.)

There are good reasons to keep the show and the chorus within our own history. First and foremost, its unlikely an Addams cousin or distant relative would have their corpse relocated. The Addams clearly have a long ancestral line, and this branch happens to be uniquely positioned in the Western hemisphere, founded thanks to Alphonso the Enormous deeds, alongside Europe’s discovery of the New World. Thus, we see only the American side of the Addams clan. There is also something to be said that the Addams are a creation of this country, unlike their counterpart of the Munsters, which harken back to European tales. The Addams are the original American gothics, and the commentary and satire Charles Addams infused in them is one aimed squarely at our culture. Additionally, the inherent political conflict between the Addamses and the Beinekes, is targeted mostly for American audiences, from mentions of swing states, creepedout left-wing Spanish weirdos, the TSA, and the so-called ‘real America.’

In the ancestors we might see a reflection of our history as much as reflection of the Addams family’s lineage. One that highlights New York and New England as well. That is the prescribed backdrop after all, the New York City skyline. And who could be better to represent all the wonderful weird of that city, than the Addamses? This isn’t to say the family, or their practices, are the cultural equivalent of wonder bread. From the 1960’s show onward, the Addams celebrate non-white, non-euro centric cultures. From eastern artifacts, non-judgmental interactions with African beliefs, to the iconic speech of Wednesday in Addams Family Values on the erasure of native peoples’ plight from the American narrative, this family is for the underdog, for the under-represented or the othered.

Functionally, the ancestors are a Greek chorus, adding pressure when needed, offering viewpoint occasionally, but otherwise observers, like the audience. One can extrapolate that the audience too are presumed members of this deceased group. Only the Addams can see the spirits, and not until the dumb show marriage curtain call, can the Beinekes see them as well—once they are officially part of the family. The show happens to open precisely as the Addams raise them and ends on the triumph of love. It is no mistake Fester is both wrangler of ghosts and narrator of the tale, making him in charge of both. While the Beinekes speak and sing to other characters, asides and songs sung directly to the audience are exclusively the domain of the Addamses. (A few moments, such as Grandmama’s flirtation with audience partially dismiss this—but not entirely).

Casting the audience as dead people is certainly an odd choice but can offer solutions to the production. Rather than all clambering out a crypt, we may find them crawling out of the audience. When Fester refuses to let them rest, the doors of the theatre may slam shut. Everyone’s stuck until the family sorts itself out, every last soul—including those with tickets.

The chorus also peoples our world, haunting the house. Here they might offer another solution, as dressing to fill a home supposedly bursting with reverent of the past. Permission is given in perhaps the most tongue and cheek way—the play makes them play trees in One Normal Night, the epitome of using actors as scenery. Rather than trees alone, these ghosts can pose behind frames acting as their own portraits, some might stand as full statues or busts (if a shelf is carved to allow an actor to slide into place), some might pop their heads through wall mounted hunting trophies, and the caveman might lie on the ground as the rug,

The Addams Mansion.

How is their house like a museum? It is populated with the debris of generations, the efforts of careful keep-saking, not hoarding. Reverence for those that came before, with an Addams twist. Their family album, a large dusty tome, replete with a few padlocks tells this tale. But the Addams’s home is relic itself, it is their family, so anchored in the past it can’t help but tell their story. It should be condemned, but for the love that holds it together. It is history seen. Past the dusty and cobwebbed artifacts, the layers of wallpaper rip away to reveal the years. Deeper still, plaster gives way to laths and furring strips, maybe old wires and implied secret passages; down to the beams themselves, which both close off playing spaces, and open for the movement of the ancestors. A collage of the past, in which most of the Addams are firmly stuck, which with ingenuity, makes the set busy for atmosphere but relatively lightweight for transitions.

With mobile set pieces, a jigsaw nature of the mansion could be created, giving the sense the place is as endless as an M.C. Escher drawing. Considering crossover scenes and quick pace, locations may reveal new dark corners through a rotation of one element and the use of stage left and right wagons, loaded with the appropriate bed, chaise lounge, or half of the dining table. The movement brings the mansion to life, like the ancestors themselves, and can create a sense that, like it or not, the Addam’s family is changing. The rundown nature captures a family unwilling to change and their sense of tradition. It can withstand a tornado but looks like ones already hit. Yet despite its disintegrated state, its foundations, as is true for the family who lives within, are firm. Somehow, it’s not a typical fright-filled haunted house. It’s a family friendly version of one.

Stylistically, Disney’s haunted mansion is a home base, with another standard found in Hogwarts from the Harry Potter series. Both being fictional places steeped in history, fantastic, but grounded in reality and one safe for little ones. Although there is no direct written evidence Charles Addam’s work inspired the amusement park attraction, there are peculiar similarities. The primary artwork of imagineer Ken Anderson, which would inspire the ride’s Grand Ballroom, was a direct copy from one of the New Yorker cartoons—and not the sole example. Other Disney sketches resemble Charles Addam’s panels, be them paneled molding up to chair rails, portrait galleries, and even the main doors of both fictional buildings. Look no further than Disneyland Paris’s version of the ride, The Haunted Manor, a full-scale crib of the Addams’s estate.

Of course, the original interiors seen in the New Yorker borrow from the artist’s own experiences, living in a New Jersey neighborhood where old Victorian mansions sat idle and went to seed. In fact, as child he broke into one of them, which just so happened to be the sight of a murder. What could more Addams?

The collection of torture devices. Charles Addams was an eccentric, and beyond his interest in the macabre, women, and cars, he collected weaponry and implements of torture. Without question this is where the playroom and the grotto come from. I favor caution at making the house décor purely from instruments of death, hoping that each room discovered uncovers the misshapen perspective of not only the family, but the primary occupant of the room.

The grotto, for instance, is Gomez’s man cave, filled with torture devices, but perhaps other twists, a pinball machine made from an iron maiden, a skeletal pin up, a dart board covered in daggers, switchblades, and axes. For Morticia’s boudoir, silks and gossamer, urns of past relatives (for her makeup, the one gag which I feel truly works from the animated movie). Perhaps for the playroom, we fly in beheaded dolls, symbols of Wednesday innocence, in undergoing death scenes such as hanging or an electric chair or poked to ribbons like voodoo dolls. The one offs, such as Pugsley’s room or Grandmama’s cart are also ripe for this visual story telling, if we choose a highly-detailed path forward. I don’t wish to hamper and over guide creativity, but there are countless hours and pages of background to mine for these embellishes which add to the over character and characterization of the show.

A Picnic in a Graveyard.

Tone fits somewhere between Sweeney Todd and Suessical, with danger of going too far in either direction. The Addamses are desaturated and gloomy in similar ways to the likes of Tim Burton. However, unlike the works of Burton, which are moody, depressed, and embrace death for different reasons, The Addams are more entrenched in the past and see death, pain, and darkness, not simply as inevitabilities, but as hobbies, sources of togetherness, and unifiers of life and love.

In the 1990s, Wednesday, thanks to the portrayal of Christina Ricci, became a cultural icon, a character to whom many who embrace the goth aesthetic and perspective idolize and model themselves after. It’s easy to forget, that she, that child of woe, who does fit with Burton’s mood, is not the full representee of the tone of the Addams together. In fact, we never fully get to see that Wednesday in the musical—she’s already started her transformation. Goth nor emo are not the answers for us.

Unfortunately, there is no easy comparison in tone, when done right. Often, I find myself falling back into circular logic: The Addams are simply the Addams, of a universe without parallel, something that is already part of the cultural grain. Beyond the boundaries of the barber of Fleet Street and Horton’s Who, inversion’s may prove useful. Pippin, with its sweet story on the surface hiding a sinister plot, is very nearly the reserve of this show, dark and torn, sheltering warm love inside. Batboy the Musical certainly pushes the limits in similar ways, with a bizarre plot that otherwise contains a standard love story, but challenges and askes more from the audience than Addams. While shows off of I.P’s, like Matilda offer a timeless whimsy and some shadow, but do break format, something Addams, does not. I don’t believe we are at the level of camp in Rocky Horror, nor in the cartoonish Shrek. Nor is it rooted in social commentary like Urinetown, or the reimagining of Wicked. The closest fit is Little Shop of Horrors, although its humor is not dark in premise but riffs on darkness. And instead of riff off B-movie plots, the musical is, what the original directors described as ‘an off-beat 19th Century Gothic.’

Which, if it is, Addams is many counts off beat of that narrative tradition (not in a musical sense, which delightfully introduces us to the family on an upbeat). Instead, the show lives in the realm of 19th century middle class drama, wearing the trappings of the Gothic. It lives nearer, for example to Lippa’s Big Fish or the film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner than it does Phantom of the Opera or Dracula. It’s melodrama, a blend of the gothic and domestic variety, but thankfully, with a broken formula using Addamses take on purity, virtue, and their unique moral compass.

The story itself is an old one with the protagonist family set in their ways of tradition, celebrating the past (Not unike Fiddler). As such, the musical is hardly the avant garde. It’s old fashioned. The line dances in the opening number aren’t modern, there’s not a cellphone to be seen, it uses tango, vaudeville, and Fester’s rocket isn’t ripped from NASA, but from Melies’s A Trip to the Moon. In general: plotting, song, and dance trends seen in the show, get no further than 1960, nor should they.

Taken together this anti-conformist family is dunked into one of the most cliché forms of theatre, and it should become a playground to see how they pervert the convention. For instance, the vaudeville/folly-like charm song, The Moon and Me, might traditionally steer toward the spectacle of beautiful women dancing, but its Fester in a one-piece whose elegance is focused upon. The confessional love song, Pulled, includes torture. Morticia sings the comment song of Death is Just Around the Corner, not to another, but to herself and maybe a little to Death itself. Borrowed too from turn of the century melodrama, beyond the bourgeois story of secrets, the script makes practical use of the traveler, a convention to aid transitions. And just like 19th century melodrama, Addams offers a gauntlet of theatrical spectacle to navigate popular in that time: smoke machines, pyrotechnics, scenic devices as well as flying scenery.

Ultimately, when finding our way through this production, be it design, music, choreography, technology, or characterization consider melodrama and its contrary. Like taking a Victorian tradition on its head. Or more apt, like picnicking in a graveyard. A favorite of Charles Addams.

Images and Visual Style

Lived-in and ‘died-in’ house.

History and ancestry everywhere.

Embraced decay.

Function and utility of items well-past contemporary use.

Un-repaired everything.

A happy home for vermin and spiders.

Layers of family going back centuries.

Different periods and styles pealing back to see older one.

Original Victorian architecture.

Nothing more modern than the 1920/1930s.

Allusions and easter eggs for devotees.

Set and ancestor costumes echoing each other:

In eras.

To integrate and ‘hide’ the ghosts when chorus should fade away.

Fluid scenic changes to keep comedic pace.

Build upon 19th Century melodrama conventions.

Consider segues not scored change music.

Embrace the kooky, with purpose and subversion.

Every normal thing is a weird version.

Maintain Addams’s original vision and satire.

Characters love the gothic and morbid, but are real people.

Model after the New Yorker cartoons.

Pallid complexions, sunken eyes, instantly recognizable characters.

Ghosts from easily read eras.

Beineke’s that are immediately identified as uptight conservatives.

But the ‘normals’ are people too.

Clash between ‘real America’ and the Addams.

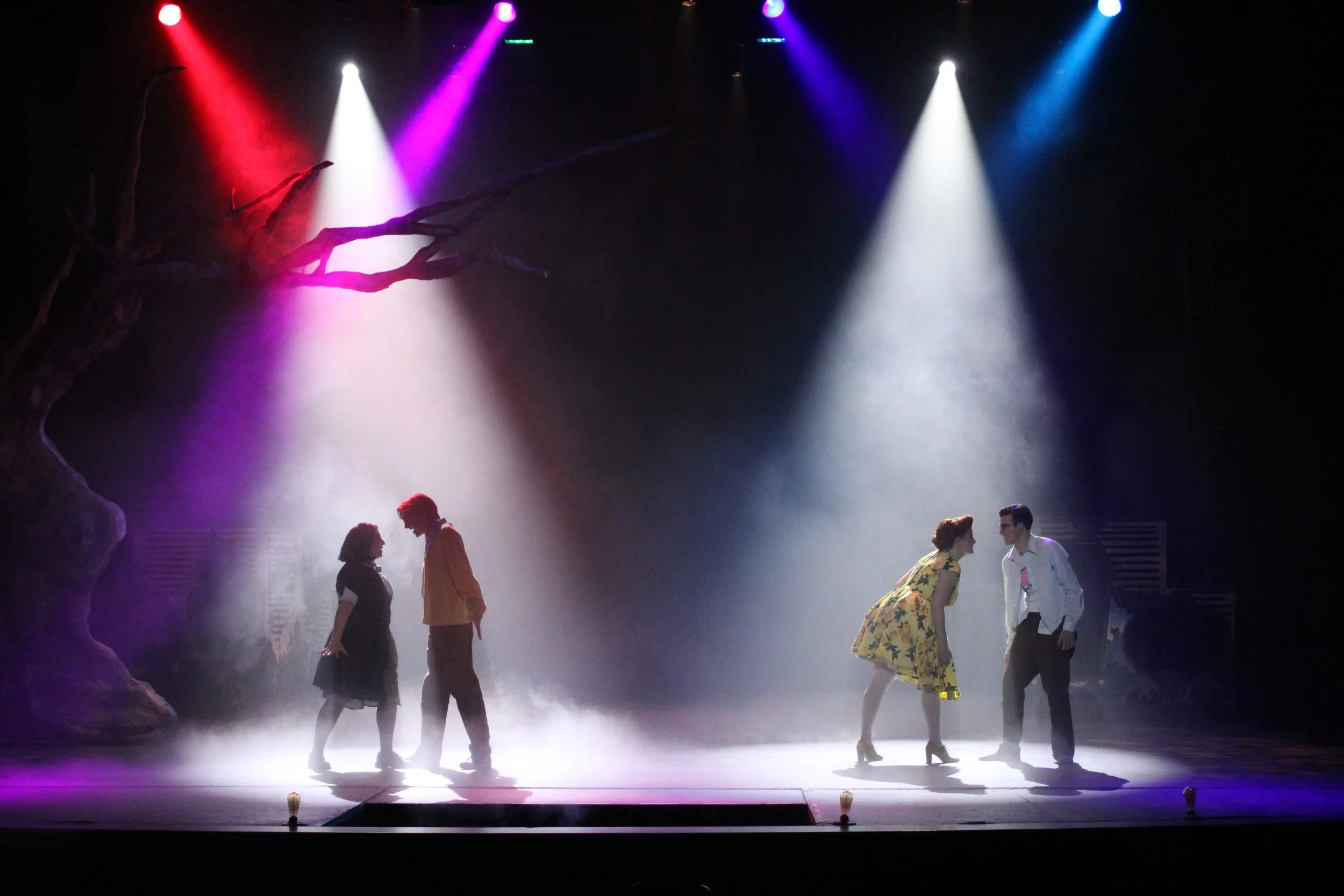

Dark desaturation highlighted by moonlight, old electricity, candlelight, and maybe a play on limelight or even footlights.

An ever present moon, see through the cracks, beams through the dust.

Moody but never scary. No nightmares.

Haunted Mansion-esque.

Caution with color, with sets and costumes we’re never out of the Addams’s domain.

Sets up Wednesday’s costume shift in scene 4?

Lights used for allusions to previous musicals, dances, semi-concert like at times?

Adhere to standard musical comedy traditions.

Allude to their roots and offer homage to their history.

A musical that the Addams’s nature resists.

Allow for playful spectacle and surprise at every turn.

Filth rich and richly filthy.

Avoid minimalism, theatrical detail wherever possible.

Judicial maximalism with use of all parts of set construction.

Support beams.

Wall sconce wiring.

Use all parts of the beast when possible.

Cobwebs, grime, and dust on priceless artifacts

The look of foreboding, but never the feel.

Images

A picnic in a graveyard.

Happiness despite the outward appearance.

Inverted with Beinekes.

The opposite of Normal Rockwell.

The Nightmare by Fuseli.

Hieronymus Bosch.

The Scream.

A well-worn chair with many rusted handcuffs attached.

That sweetie, Norman Bates, his house, and loving mother.

And of course, the original Addam’s cartoons.

Design qualities for consideration

Black ink washes.

Materials that don’t age well:

Rust-eaten wrought iron.

Molded, termite-infested, weather-beaten wood.

Ancient, cracked plaster.

Flayed layers of wallpaper down to the bones of the building.

Contrast between the bright and dark

A home that won’t change against bright Modern New York against an inky sky.

Pale skin, dark hair, dark clothes

Primaries for hollow cheeriness, deep rich color and darkness for devotion

Beauty in grotesquery

The Addams in a musical of all things.

The Why of it All

Academically, it’s a quick history lesson on the melodramatic form, emphasizing its aspects through a counterpointing narrative and resistant characters. The Addams Family Musical is, in its own weird way, a celebration of spectacle and theatricality, both using the traditional and subverting it as it goes on.

As a piece of entertainment, it’s a joy loaded with challenge and spans a divide in our culture. It’s a romp of a play that just skirts distaste, available for whole families, even with echoes of the prevailing Utah culture. Many see themselves in the Addams, whether it be a mirror to their own family’s bundle of oddities or individuals who find affirmation in being different, finding love in non-traditional places.

In terms of commentary, it is timely. The play promotes common ground for differing opinions and perspectives. Politics be damned if we can get along, in the face of love, for the sake of family. But the musical, like all Addams stories, leads us to the conclusion that conformity is a fate worse than death. Think and feel for yourself, it proclaims, in opposition to the orthodoxy, the cultural winds, and even your own family’s wishes.

Personally, it inspires me with an optimistic fatalism. We’re all bound for a plot of earth eventually. We should embrace life, love, and darkness (ie the unknown future), honor those unique things that make us who we are, and others who they are. Why would you spend time on anything else? Why settle for anything less?

At its heart, we’ll succeed if the audience laughs, loves, and goes on a surprising ride. Many will see a standard musical, enjoy the music, the flashy dance, the marvelous voices, and the moment of it. Others will enjoy the retelling and references of all things Addams. Hopefully, they’ll talk of all the special quirks we lay as traps to snag their attention but miss those snares of the heart beyond Happy Sad: the sheer passion of the last Tango that makes one wish for a romance like Morticia and Gomez, the power of truth seen in Full Disclosure, the success of the hopeless romantic Fester as he’s shot to the moon.

And maybe some might see acceptance and some might change their resistances to others not like themselves. Those are things, we might truly hope for. And are things, I dearly wish, they take to their graves.

Snap Snap.